What Supercompensation Taught Me

For most of my adult life, I thought being sore meant I was doing something right.

Aches, stiffness, the feeling of dragging my body around — I took all of it as signs of progress. They were proof I had worked hard, that I was pushing myself. And that belief wasn’t just about climbing or strength training. It was baked into how I approached work, life, and effort in general. If I weren’t a little burned out, I wasn’t doing enough.

It turns out that the entire mindset was off.

Recently, I started digging into the science behind training adaptations. I had AI walk me through the concept of supercompensation — the process by which the body builds back stronger after a well-timed dose of stress. That led me into related concepts I hadn’t fully understood before: sympathetic vs. parasympathetic tone, and catabolic vs. anabolic metabolism. It all clicked into place.

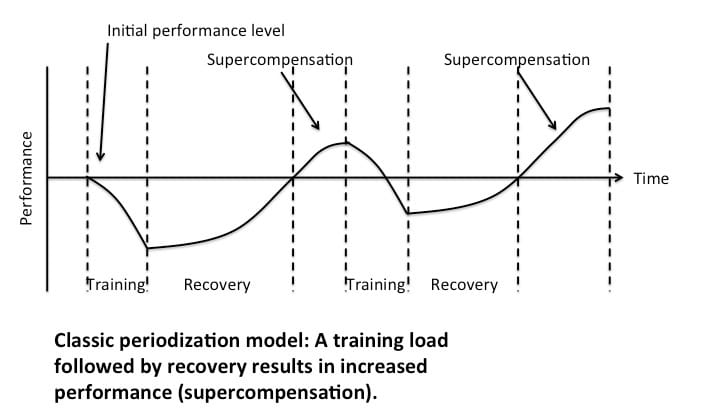

Here’s the core idea: your body doesn’t get stronger during training. It gets stronger during recovery. Training is just the trigger — a sharp, calculated disruption to your baseline. What matters is how your body responds in the hours and days afterward.

In a healthy recovery cycle, the body reacts to stress by first breaking down (catabolic) and then rebounding (anabolic), overshooting the baseline slightly. That overshoot is the gain. You’re now just a little stronger, more coordinated, or more adapted than before. But to benefit from that adaptation, the timing has to be right. Push too soon, and you interrupt the rebound. Wait too long, and the gain fades.

It sounds simple when you write it out: spike the system at regular intervals (every 3–7 days, depending on the intensity), and let recovery do its job. If you keep hitting that curve at the right time, you ride the wave of improvement.

But I wasn’t doing that. I was just stacking stress. I thought my body always needed to feel worked, or the training didn’t count. I’d climb hard, and then feel flat or tired, and mistake that flatness for weakness. So I’d climb again, trying to “wake myself up.” I’d use stimulants, pain killers, and sheer willpower to push through, and I often got away with it... until I didn’t.

Eventually, I started noticing the patterns. Poor sleep. Chronic soreness. CNS fatigue masked as a lack of motivation. I realized I was spending more time recovering from training than actually improving because of it.

So I’ve started to experiment with a different approach: training hard, then deliberately aiming for full recovery. That means rest days that feel boring. Days when I wake up with zero soreness and think, “Did I even train?” It’s counterintuitive. When my body feels calm and normal, I assume I’m detrained — like I’ve lost my edge. But that calm, neutral state? That’s what readiness feels like. That’s when I’m capable of a peak performance.

It’s a hard shift to make psychologically. Our culture doesn’t reward calm or inactivity. It rewards output, intensity, and doing. Even in climbing, there’s this subtle pressure to always be “in season.” Rest days are framed as necessary evils. It’s rare to hear someone say, “I feel great — I’m fully recovered,” and believe them. We assume recovery is something you have to earn by first destroying yourself.

But now that I’ve experienced the other side — what it feels like to walk into a gym rested, calm, and slightly under-stimulated (yawning sometimes), and then surprise myself with what I can do — I’m trying to trust it more. I’m learning to recognize that ready state: the lack of inflammation, the lack of tension, the quiet sense of control in my body.

Written with help from ChatGPT